For Chinese, lessons in Philanthropy 101 in the U.S.

This article originally appeared on Philly.com

By Jane M. Von Bergen, The Philadelphia Inquirer –

PHILADELPHIA — Given the growth of China’s robust economy, the Chinese clearly know how to make money.

They aren’t quite as good at giving it away.

In 2010, America’s 308.7 million people contributed $290.98 billion to charity. In China, where the population topped 1.3 billion, donations reached a mere $16.4 billion, according to an official Chinese website, China.org.cn.

“China still needs to cultivate the nation’s awareness of philanthropy and set up a more complete system to develop the cause,” Minister of Civil Affairs Li Liguo said in announcing new charity regulations in March.

What seems so natural to many of us — putting money in the plate at church, writing a check, contributing to the United Way through payroll deduction, incorporating donations into a tax strategy, feeling an obligation to give back — doesn’t happen in China.

Nor, however, does China have the kind of extensive charitable infrastructure that makes it easy for us to give.

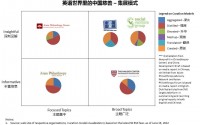

In the United States, tax deductions, charitable bequests, and public filings promote transparency. Though imperfect, watchdogs and advocacy groups monitor charities’ finances. In China, all that devolves to the government and its officials, who have been trying to figure out how U.S. charities can operate with so little control.

That’s why the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy and Practice has hosted groups of Chinese officials eager to learn Philanthropy 101 — U.S. style. One group was here in late March; another will visit in June.

Organizing the visits was Tianxue Qiu, of Beijing, a graduate of Penn’s master of sciences program in nonprofit leadership.

While here, Qiu received grants to bring Chinese government officials to Penn so they could learn from, among others, her dean, Richard Gelles, and one of her teachers, Eileen Heisman, who heads the Jenkintown, Pa.-based National Philanthropic Trust, which manages $1.1 billion in assets and dispensed $143 million in grants in 2011.

“What is the best way to utilize what I learned?” Qiu asked rhetorically in a morning interview on Penn’s campus last week, three days before she was to return to Beijing to start a consulting service for nonprofits and nongovernmental organizations.

“I could go back and work for one organization, but I would have a limited impact,” she said. “I want to change the mind-set of the government.”

In China, Qiu said, most charities, including big names such as the Red Cross Society of China, are almost arms of the government, which licenses them. Without a license, they can’t solicit donations.

Nongovernment grassroots organizations have sprung up, but they can’t solicit money, and their ability to operate is tenuous.

“If the government is not happy with what you are doing, they can close you at any time,” Qiu said.

At the same time, there is increased public interest in charities, fueled, in part, by the growing number of rural families moving to Chinese cities for work. The law requires people to receive education and health care in their birth towns, with the result that millions of children now are going without.

But what sharpened China’s philanthropic focus was the 7.9-magnitude earthquake in Sichuan province in 2008 that killed at least 70,000.

Donations poured in to Chinese charities, Qiu said, but questions arose about how the money was spent: “There is no transparency.”

By contrast, U.S. charities must file Internal Revenue Service Form 990, showing which proportion of revenue is spent on helping others, not on overhead.

The Chinese officials visiting Penn “seemed to have a hard time getting their head around the idea of philanthropy without government,” Gelles said.

For example, Gelles said, they asked: “Don’t some of your nonprofits exist to agitate against the government?”

Yes, he explained, some nonprofits do work to change government policies. It was a strange idea, he said, to a government “whose knee-jerk reaction is to repress.”

Heisman, who talked for eight hours, said the group very politely asked her the same question about 10 different ways.

They wanted to understand the relationship between an executive director, like herself, and the board, and how both could operate without government influence.

“It’s so counter to how their world is structured,” she said.